ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND CREATIVE CHARACTER: US COPYRIGHT OFFICE LAYS DOWN RESTRICTIVE RULES

13/03/2023

On 25 February 2023, the United States Copyright Office (USCO) issued a landmark decision concerning the protectability by copyright of results achieved by means of AI, concluding that this protection cannot be granted to material created by AI in a non-predictive manner, i.e. not controllable in its expressive form by the user/author (https://www.riaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/AI-COPYRIGHT-decision.pdf). In reaching its decision, the USCO analyses in great depth and detail the requirements for the recognition of author protection, expressing extremely interesting assessments of the notion of “idea” (not protectable) and “expressive form” (protectable), the scope of which may well go beyond the boundaries of the AI, and instead concern the entire copyright system.

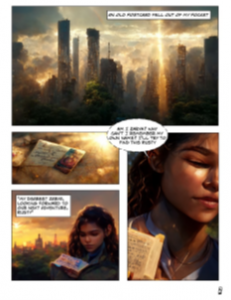

To better understand the USCO’s decision, it is important to keep in mind the type of work of art whose protection was claimed (entitled “Zarya of the Dawn”), as well as – above all – the method of operation of the AI used in its creation. ‘Zarya of the Dawn’ is a comic book, consisting of eighteen pages, including a cover page. The cover features a picture of a young woman, as well as the title of the work and the words ‘Kashtanova’ and ‘Mid Mid’ (referring respectively to the name of the designer who intended to record the work, Kristina Kashtanova, and to the name of the AI she used, i.e. Midjourney). The other pages of which the work was composed consisted of mixed textual and visual material (in other words, graphic images accompanied by captions: see below the images taken from the USCO decision). According to the applicant’s own statement, all the images used in the work were created by Kashtanova through the use of Midjourney technology, which consists of a subscription service that allows users to pay to generate images, with subscription plans corresponding to the time used to generate the images. In concrete terms, the user – once subscribed to the service – generates a text message expressing the requirements of the image to be generated by the AI. It is also possible for users to indicate a URL of one or more images to influence the output generated by the AI, or to set parameters that provide functional indications. Following the prompt entered by the user, Midjourney generates four images in response, which – by means of a grid and buttons – can be managed in various ways, e.g. to obtain a higher-resolution version of an image, to create new variants or even to generate four new images from scratch. According to the examples provided by the USCO, by entering the command “/imagine cute baby dinosaur shakespeare writing play purple” the AI provides four different images, in any case referring to puppies, dinosaurs, the color purple, and Shakespeare. However, the images have different (expressive) characteristics, as the puppy has specific shapes, colors, proportions in each of the images (see image from the USCO decision below): In this context, the USCO particularly emphasizes the circumstance that the instructions given by the user to the AI do not concern the realization of a particular expressive result, but simply indicate in broad terms the objective to be achieved. Moreover, the way Midjourney operates is peculiar in that it actually converts the words and phrases contained in the user prompt “into smaller pieces, called tokens, that can be compared to its training data and then used to generate an image.” The generation involves Midjourney starting with “a field of visual noise, like television static, [used] as a starting point to generate the initial image grids” and then using an algorithm to transform them into human-recognizable images, according to its own training data and matching them with the user’s specified features. The latter, however, does not control the creation process by the AI, because it is not possible to predict what the images actually generated by Midjourney will be, in terms of expressive elements. In practice, of course the image will be that of a baby dinosaur writing a play, as Shakespeare might have done, where the visual connotation is that of purple; but no one can determine whether the baby will be tall or short, thin or strong, smiling or worried (or expressionless), with sweet or threatening shapes, etc. It is therefore a completely different way of working than the typical creative way of working of the author/artist, even when the latter uses an instrument, since in all these cases it is the author/artist who controls the instrument itself, and who knows which elements to use to realize the work they have in mind. In the specific case of the work “Zarya of the Dawn”, the USCO therefore concludes by limiting the copyright registration to the textual parts of the work itself (the captions commenting on the images), and to the activity of selecting and arranging the images used for the composition of the book, denying protection to the individual images. In the case of the texts, the USCO’s decision appears to be obligatory: the designer had in fact affirmed (and was not questioned by anyone) that the texts of the captions had been created directly by herself. With regard to the selection of the images, the USCO accepted the designer’s claims that her creative process had consisted of generating a series of images by means of AI, which had then been carefully selected and organized by her in order to create the whole constituted by the story told in the comic strip. In both cases, the activity carried out by the designer is considered sufficient by the USCO to confer copyright protection, since there is creativity (albeit minimal), and the author is a natural person. On the other hand, protection is denied to individual images created by the designer through interaction with AI. According to the USCO, in fact, although the designer claimed to have ‘guided’ the structure and content of each image, the process described made it clear that it was the AI – and not the designer – that gave rise to the ‘traditional elements of authorship’ of the images. The fact that the designer had entered the prompts to obtain the images, and then had chosen one or more of them for further development by modifying the prompt or other inputs provided by the AI did not constitute for the Office enough evidence of sufficient creativity of the work. This is because the process envisaged by the AI is a series of trial and error until, in a random way, the image generated independently by the algorithm comes close to the designer’s original vision. According to the USCO, therefore, rather than a tool that Ms Kashtanova controlled and guided to achieve the desired image, Midjourney generates images in an unpredictable manner. Accordingly, the users of Midjourney are not the ‘authors’, for copyright purposes, of the images generated by the technology. As the Supreme Court has explained, the ‘author’ of a copyrighted work is the person ‘who actually formed the image’, the person acting in an ‘inventive mind’ capacity. The person who provides textual suggestions to Midjourney does not ‘actually form’ the generated images and is not the ‘mind’. In dealing with the specific issue of textual prompts by the designer to the AI, in order to deny protection, the USCO addresses the issue of the distinction between the ‘idea’ and the ‘expression’ in the intellectual work, reaching in my opinion innovative results of particular interest that extend beyond the scope of the AI, to invest the entire perimeter of intellectual works protected by copyright. Indeed, the Office considers that the prompts given by the designer to the AI function more as suggestions than as orders. In this (the comparison is by the USCO) they are similar to the situation where a client engages an artist to create an image by giving the latter general indications as to the result that should be achieved. In these cases, the author would be the visual artist who received the instructions and independently determined the best way to express them. Thus, the commissioner would provide the (unprotectable) idea, while it is the visual artist who generates the expressive form of the work, and thus receives copyright protection. In concrete terms, the artist would carry out the activity that in the specific case considered by the USCO in its decision of 25 February 2023 is that carried out by the AI, which however – not being human – cannot aspire to the status of author and therefore remains unprotected (as for the output, since the technological system of which the AI consists is well protectable with patents or secrecy). Interestingly, a similar issue was also recently addressed by the Court of Paris, in the case that pitted the well-known visual artist Maurizio Cattelan and his former collaborator Daniel Druet against each other (Court of Paris, judgment of 8 July 2022). Druet is the craftsman that Cattelan used to create some well-known works, such as the ‘Ninth Hour’ (a wax sculpture depicting Pope John Paul II on the ground, struck by a meteorite). Druet asserted in court that he was the co-author of Cattelan’s works, because the latter had only given him vague instructions, and moreover had publicly stated that he was unable to draw, paint or sculpt. According to Druet, therefore, the concrete expressive realization of the work of art was mainly attributable to him. In the proceedings, Cattelan’s defense counsel had, in particular, argued that the realization of the intellectual work is secondary to its conception, particularly in the field of ‘conceptual art’, in which artists often imagine their works but do not create them themselves. In this particular case, the Court – also for procedural reasons – denied Druet’s application, considering that Cattelan had provided sufficiently specific indications for the location of his works (in particular, choice of building and size of the rooms to suit the character of the work, direction of gaze, lighting, destruction of a glass roof or parquet floor to make the installation more realistic and suggestive). However, it did not pronounce ex professo on the main issue, i.e. what activities and choices a person has to make in order to qualify as an author, when they use a third party, or an instrument (including AI), to realize the work of genius. Applying the considerations made by the USCO (and also following the tendency indicated by the decision of the Paris Court in the Cattelan case), the thesis put forward by Cattelan’s lawyer should be refuted. Indeed, it is not enough, even in the field of conceptual art, to merely “conceive” a work, or – in other words “have the creative idea”. Instead, it is necessary to intervene in the concrete expressive choices, establishing the specific characteristics that the work must have, so that – if it is a visual work – one must clearly establish what its dimensions, shapes, proportions, placement, colors, materials used and various components, and so on, must be. Simona Lavagnini